Let’s do Lunch with Oliver Friggieri (2003)

A prolific author whose work has been translated into numerous languages, he has done more to promote Maltese literature and culture at an international level than anyone else in his field. JOSANNE CASSAR meets PROF. OLIVER FRIGGIERI for lunch at his home in B’Kara

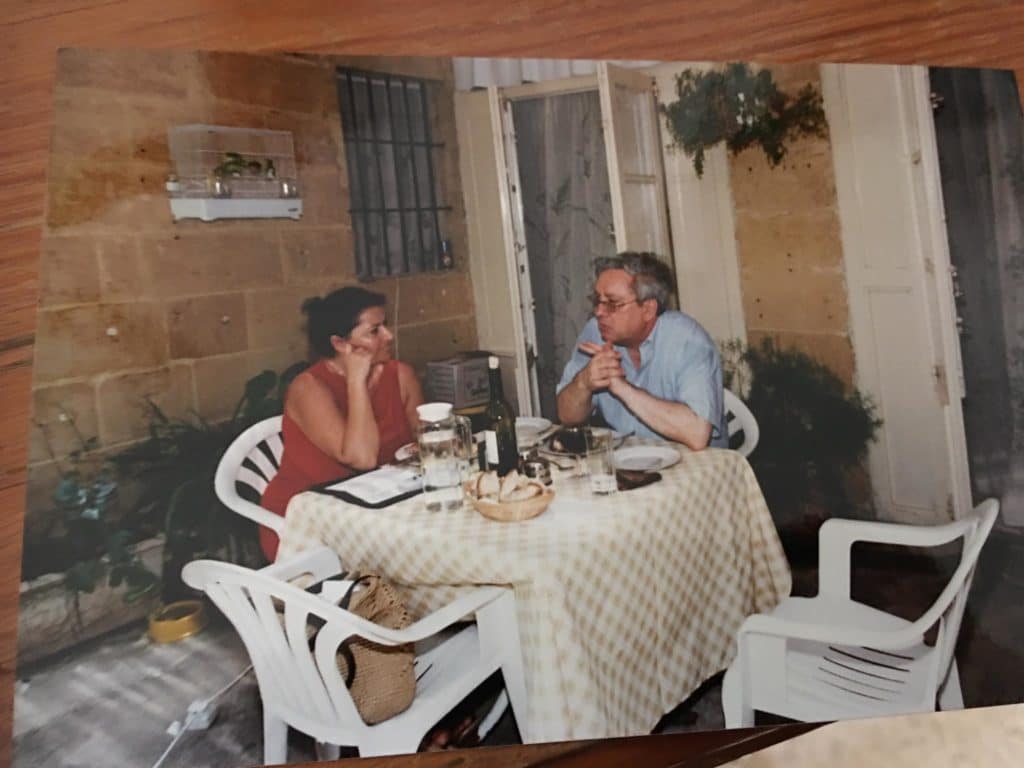

Prof Oliver Friggieri declined my invitation to go to a restaurant of his choice. Instead, he invited me to his home, saying he would feel more at ease that way.

This statement, perhaps more than anything else, captures this man’s quiet nature. A man who loves simple things and a tranquil, hushed way of life, surrounded by his beloved books in an old town house in B’Kara.

Walking into the cool back yard filled with plants, shaded by a traditional hasira, it seems like I have stepped back into a Malta of a different era. His wife Eileen has graciously made us a home-cooked meal beginning with a cream of vegetable soup, and in the quiet stillness of this hot summer afternoon, Prof. Friggieri starts telling me about his life.

Born in Floriana, near the harbour, the family then moved to the relatively depressed area known as Il-Balzunetta when he was eight years old.

“For a time, it was considered a sort of red light district. It is in front of the Police Depot, near the Mall, the Seminary and ix-Xaghra, so you have justice, entertainment, the garden and sport and contained in the middle of these four ‘institutions’ you have Il-Balzunetta. My recent novel Gizimin li Qatt ma Jiftah is about that period, a reconstruction of the late ‘50s.”

Recently, he admits, he has been harbouring a feeling of nostalgia for those long ago days of his childhood. The more he sees Malta changing at such a frantic pace, without control, the more he feels the need to register the Malta he remembers before it disappears forever.

“It was a very traditional upbringing: we went to Il-Muzew and studied. My father worked with the British Services and was rigorous about everything: each penny he spent, the time we went out and came back home. The discipline of the British! He always brought The Times home and we were encouraged to read in English as well. My father influenced me, despite his detachment and his seriousness. He loved us at all costs, a modo suo. We were four children, but one of the girls died as a baby and that affected me a lot. I discovered that it is possible to die before your time – it is a theme which comes up a lot in my work.”

His mother, from Cottonera, was “a timid woman of great simplicity” who had a hard life when she was young.

“For me she always represented that which is good. She was resigned to life, a woman of very few words who believed you should always count your blessings. I only kissed her once, when she died, because at the time it was almost taboo to come close to your mother and touch her. She influenced me because she was so ‘average’; she was just herself. I think the love I have for the Maltese language comes as a result of this democracy: wherever I see the language being pushed aside, I feel that there are Maltese people being pushed aside.”

Hearing Oliver Friggieri speak, using his deceptively simple and yet so eloquent choice of phrase, it is easy to believe that he was born to be a writer; a wordsmith. In fact, he has been writing poetry since he was 12 years old (“I’m not saying I wrote well, but I wrote”).

And yet, his first calling was completely different.

“Ever since I can remember, my wish was to become a priest, and I still have a certain yearning for that way of life,” he says of his days spent at the Seminary. This has re-emerged in my latest novel It-Tfal Jigu bil-Vapuri.” Out of the 40 who were in that course, half eventually left and went on to get married like Prof Friggieri himself.

“I felt that the closed atmosphere of the priesthood wasn’t for me, although I greatly admire those who chose it.”

He went on to University to satisfy his unquenchable thirst for more study and research. After obtaining his BA in 1968, he taught Maltese and philosophy in state schools. Then he read for an MA and later a Ph.D. in Maltese literature, the first person to do so. In fact, both his theses were written in Italian and later published in Italy. “I know more about Dun Karm than I know about anyone else!”

And always, he continued to write and write. He readily agrees that his family background, particularly his father, continues to haunt his work, especially his novels.

“Without realising it, when you write, your subconscious brings to the surface all those things from your past. It’s like when you put your hand in your pocket for a hankie and you bring up a button that has been there for two years. That’s what happens with writing, I think, once you dust off your subconscious it comes up by itself, and you never know what will appear.”

Mention the name Oliver Friggieri to most people and he will seem irrevocably linked to their schooldays, when they went through some poem or short story of his. The perception many have of him is that he is a very serious, studious man who writes ‘heavy’ literary works.

But when I mention this to the man himself, he is clearly not happy with this perception.

“I really don’t like that image of myself, even though their perception might be occasionally correct. When I write literary critiques, yes, they may seem difficult, but when I write short stories or novels, the language I use is very simple. Even poetry has to be very clear, because what is the point of writing something which no one else understands? There is a difference between scientific research which is written for a few experts, and what you write for students to engage their emotions, to make them laugh or cry.”

You cannot interview Oliver Friggieri without broaching the inevitable subject of the language question in this country. However, he makes it clear from the outset that he is uncomfortable with discussing the significance of the Maltese language.

“I don’t blame you for bringing it up, but really, it should be taken for granted. It belongs to the past. It’s as if you are asking me, ‘do you eat?’ In a way, it’s humiliating. What are other countries doing? Why should the importance of Maltese in our country be any different to the importance of Danish in Denmark, for example? We still have a very long way to go before Maltese is given the stature it deserves, but I don’t wish to discuss it. It’s degrading, especially now that we form part of the EU. Not from a linguistic point of view, but from a psychological aspect. Even someone reading this will say ‘are they still discussing their language?’ It’s so obvious, it’s like discussing your identity, your nationality, whether you are Maltese or not. In fact, I really wish you would leave this out. The pattern is European and therefore things should be obvious. The name of the game is ‘normalisation’. Europe expects us to behave the same way all the other countries do. The smaller countries have much to teach us in this respect. As in many other sectors, I believe they should be a constant point of reference. Well-defined bilingualism, the European way, is beneficial, necessary, and obvious. A national language, being the embodiment of a whole community, has one simple, acknowledged definition in Europe and anywhere else. It is universally accepted and adhered to. So has English as the unifying international vehicle. We need both languages, like the rest of the world. Let us simply comply – and march ahead.”

After some discussion, I manage to persuade him on the importance of leaving his arguments in, for it is only by stating these (perhaps obvious) points that we can all truly understand the implications.

Of course, I can appreciate his reticence. How long are we going to debate that which should not even be up for discussion?

“Once a French scholar asked me jokingly, ‘don’t you have numbers in Maltese?’ It’s bad enough we don’t have a lot of natural resources, but that we don’t even have respect for ourselves! After all, numbers in Maltese are among the oldest in existence because they are derived from Arabic. What should be done to safeguard our language? We should adopt the same criteria used internationally for all languages in Europe, which are held in very high esteem. Europe is full of lesser used languages such as ours. Their usefulness is now more evident than before. But our country still suffers from such an outdated inferiority complex…” he shakes his head sadly.

On a brighter note, Oliver Friggieri has seen a revival of interest in Maltese as a subject of study at University level where he teaches literary criticism.

“They tell me they want to discover more about their country, but I tell them they also have to discover the world, otherwise they will become insular. On the other hand, you cannot discover the world without first discovering your own homeland, because you will then disappear. We still have to find a balance between being too inward looking and being just a zero. In Europe we only stand one single chance – to be Maltese, modern, outward-looking, like all else respectively.”

Not surprisingly, he was one of those who lobbied for Maltese to be recognised as an official EU language, for political, cultural and psychological reasons, as much as anything else. It is after all, the language that gives us a separate identity as a nation, particularly a small island nation such as ours.

“Basically language makes us complete, humanly and not simply in terms of citizenship. But please, no more on this subject. Such ideas have long been divulged and accepted universally.”

You cannot blame him really, for everywhere he goes he is bombarded on this issue. It has come to the point where he no longer accepts invitations to appear on TV programmes to discuss this topic. He is genuinely heavy-hearted that the country has not moved on in this respect.

To his relief, I move on to something else. His numerous publications, which are too many to be listed here, have brought him international recognition. His work, however, has met with the occasional controversy.

When in 1986, the now classic book Fil-Parlament Ma Jikbrux Fjuri came out, it caused a stir because it was a novel with a political setting at a time when Malta was restless for change. It also caused a bit of an upset with his own father, who had always urged his son to stay away from politics.

“The book was launched at the Phoenicia lounge and I was only expecting a few of the usual people to show up (erba’ min-nies). The last person I wanted to bump into was my father, but there he was. He told me I was going to give him a heart attack because so many people were turning up they had to change the venue to the ballroom. About 600 people came and there was a very heated discussion between myself, Dr Alfred Sant, Dr Ugo Mifsud Bonnici, Fr Peter Serracino Inglott and Dr Paul Xuereb. The book sold very well. At the time, (Dom) Mintoff said, ‘those that have nothing better to do, write books’ and I was so offended! After all, my book shifted public opinion simply because I tried to depict Maltese reality, as I normally do in my works.”

After all this time, he still feels this is the one book which has been given a different interpretation by whoever reads it.

Now, another of his works, It-Tfal Jigu bil-Vapuri, is going to be turned into a drama by Net TV. Writers are always slightly possessive of their work, and it was not easy for him to ‘let go’.

“It took me three years to tell them yes,” he says ruefully. “Mind you, even when you allow your work to be translated, it is no longer yours, so I have learnt to resign myself to it. Now it has been translated into a TV script. Some people have fallen in love with the novel, and so I could not ignore that.”

Over the last 35 years, he has built a vast body of work as the leading critic of Maltese literature. This has led him to international congresses in numerous foreign countries where he has ‘flown the flag’ of our national culture.

I ask him whether it is easy to bridge the two roles of writer and critic.

“When you critique the work of others, it is a science. You take a text and analyse it, much like you would take a machine apart to examine all its spare parts. When you are writing literature it is a creative process that you can only do when the mood strikes you. In my case, I write when I am feeling tranquil and calm.”

Mrs Friggieri brings us our second course – she has made roast chicken and potatoes with stuffed marrows, true Maltese cuisine.

The nostalgia inherent in Oliver Friggieri’s work prompts me to ask whether he likes the Malta of 2003. He shakes his head:

“It is a complex question. In many respects, Malta has lost the sense of rhythm, a sense of memory – it forgets too much. It was like a parked car which has now gone full speed, but somewhere in between it needed to put on the brakes. I don’t think what I write is necessarily due to nostalgia, it’s using the past to better understand the present.”

He speaks fondly of the University where he has lectured since 1976.

“My heart has always been there, in research, in discussing. My students have always respected me, I can’t complain. I have great respect for all of them. I’m very proud to have introduced the MA and Ph.D. programmes in Maltese Literature at our University. Did you know that there are more foreigners who hold Ph.D.s in the Maltese language than Maltese people? Many more graduates are now embarking on such research at the highest level.”

Now, I can understand his heartache at the way our language is cast aside by those who should cherish it, when others are so clearly fascinated by it.

Oliver Friggieri’s creative output has intentionally slowed down over the years – he links this to the fact that he no longer smokes.

“I was a heavy smoker who quit smoking overnight. I say this to encourage others, but you have to quit for a reason that has nothing to do with your health. Smoking is just an excuse to fill a void.”

An indefatigable workaholic, he is a person who doesn’t like to waste time.

The only reason he travels is for work, to ‘spread the word’ about Maltese culture, and would never go abroad just to enjoy himself.

“For me, work is pleasure,” he replies.

I wonder how this affects his family, and he falls into a bemused silence, pondering this point as well.

So how do you relax?

“Gardening, watching documentaries, reading books about international and Maltese history.”

I suppose this is his idea of light reading.

He describes himself as someone who likes people but who prefers to invite friends to his home instead of ‘socialising’ at parties.

While his TV appearances have dwindled, he loves speaking on radio.

“It is a complete medium of communication. With television, the visual is too distracting. On radio you can stop and think, choose your words more carefully, you can take off your glasses if you wish, close your eyes when you speak. You don’t have to worry about your appearance!” and he self-consciously smoothes down his slightly dishevelled greying hair.

In his smooth, unhurried intonation you can still detect the lingering traces of his seminary training. He agrees that the formation to become a priest has never really left him.

“The main rhetoric in Malta is the rhetoric of the sermon. If you compare a politician at a mass meeting and a priest during Mass, you will find a lot of similarities. We are good, the others are evil; this is the truth, that is not the truth.”

Given his attachment to his roots, it is not too surprising that Oliver Friggieri’s wife is also from the Balzunetta area. They have one daughter, Sara, who is a teacher.

“She is very appreciative, at times equally critical of my work, ” he adds, hiding a smile.

We continue our lunch. The rest of the meal is just as traditional: gbejniet with bread, slices of watermelon, and finally a fresh lemon sorbet.

“The more I study, the more I travel, the more I meet professors and scholars, the more I appreciate people who are down-to-earth and without pretension. The common people whom no one ever knows about.”

And yet, I point out, you have made a name for yourself on an international level. Was this something you deliberately set out to do?

“Sometimes I find myself invited to things, and it just happens. I’ve spent my life studying and writing, working hard towards the same goal and the contacts came about because one thing leads to another. I don’t want to sound boastful, but I’m pleased that my work has been appreciated by others.”

Today, at the age of 56, Prof Friggieri shows no signs of slowing down. He will continue to work, lecture and write for as long as he can.

As he shows me the rows and rows of books which line his shelves, his life’s work, he explains the background which led to this translation, to this academic paper, that novel or short story. Occasionally he reads out one of his Haikus from his collection of poetry. He fingers each book lovingly – they are as precious as children to him.

“A writer writes in order to leave something behind him. It’s not egoism, it’s a need, and not everyone can understand it. As time goes by, you learn to write and speak more sparingly, to value words more, and to say things without saying them, la capacita’ di non dire.”

When I ask what he would like to be remembered for, he pauses a while before he answers:

“That whoever reads the books I leave behind, will recognise himself in them.”

- December 6, 2020 No comments Posted in: Let's do Lunch