Let’s do Lunch with….Norman Hamilton

He was the only Maltese DJ to ever present programmes on BFBS. And his smooth, melodious voice has carried him from radio to television with equal ease. His career in broadcasting has been a rocky one but he has moved on and successfully branched into the travel industry

This interview was originally published in August, 2000

“I really like this place” Norman Hamilton says of the place he chose for lunch, Trattoria Palazz, located in the capital.

“It’s nice, it’s historic. I like places with atmosphere as well as good food. I especially enjoy coming here with two or three people because the tradition is to bring you four different kinds of pasta in a platter so that everyone can have an assaggio di pasta (tasting of pasta).”

Norman knows his food as well as his wines. We decided on an assaggio of farfalle with salmon and caviar and tagliatelle with spinach and shrimps. To go with this he ordered a half bottle of Greco di Tufo, a sweet fruity wine from the Ripinia region.

The ambience of Trattoria Palazz could be that of any city in Europe. The owners have managed to create that Old World charm, with Maltese stone work, wrought iron and checked tablecloths. You descend the wooden staircase into the cool lower level to find just a few tables and rows and rows of fine wines stocked on the shelves.

While admitting he has a weakness for good food, Norman is very health-conscious. “Just watching out for all that cholesterol stuff” he says laconically.

It was 1962 when Norman, then a clerk in the Military War Department, applied for a vacancy with BFBS (The British Forces Broadcasting Services). “I had no experience, I just used to read the trade papers and listened to Radio Luxembourg. They gave me a four hour afternoon programme called Beach Party.”

Just like that? With no training?

“Well I trained in house with them.”

That is one very lucky break. Norman had always wanted to be a DJ – as a boarder at St. Aloysius he would sneak in music magazines until he was caught by the Rector who confiscated everything. He will never forget the Rector’s scornful words: “How stupid can you be? Do you think you will ever earn money from those silly things?” (Little did he know…)

Then, one day, BFBS found out he was Maltese (the surname, English accent, and the fact the he had been employed with the forces, had made them assume he was British). Their policy was to employ only British personnel. Luckily, they reasoned that they could hardly take him off the air. “Please keep it quiet” he was told.

Although he made repeated attempts to join the Rediffusion he was always refused. He decided to immigrate to England where he worked as a civilian officer for three years as a sub-editor with the Post Office magazine.

But fate had a way of smiling on Norman just when he least expected it. When someone in London who used to do a programme for Malta fell sick, he was asked to fill in. This one-off turned into a weekly programme, which caught the attention of Rediffusion head Joe Grima, who offered him a three-month contract to present a light breakfast show. “Getting into Rediffusion through the back door, so to speak” is how Norman describes it. His gamble worked; after the contract expired, he was taken on full-time.

My first memory of Norman Hamilton is his soothing voice on the radio programme Antenna. I can still recall his catchphrase every Friday that “il-weekend jibda hawn!” (the weekend starts here). But the programmes which will always remain in his heart were the breakfast show (1967-73), and Turn On, Tune In at 10am. He admits to finding it easier to present in English rather than in Maltese: “particularly the ad libbing”, and acknowledges that his style was based on what he used to hear on his beloved Radio Luxembourg.

“It was something new for Malta – no one had that style. Then Rediffusion sent me on a production course with BBC Radio 1, and I understudied with Tony Blackburn and Terry Wogan for six months. One fine day Wogan didn’t turn up and the producer said ‘you have to stand in’. It was one of the most frightening days of my life. Three hours on BBC nation-wide radio! But I did it. They offered me a contract for six months but I couldn’t because I was bound to Rediffusion for two more years.”

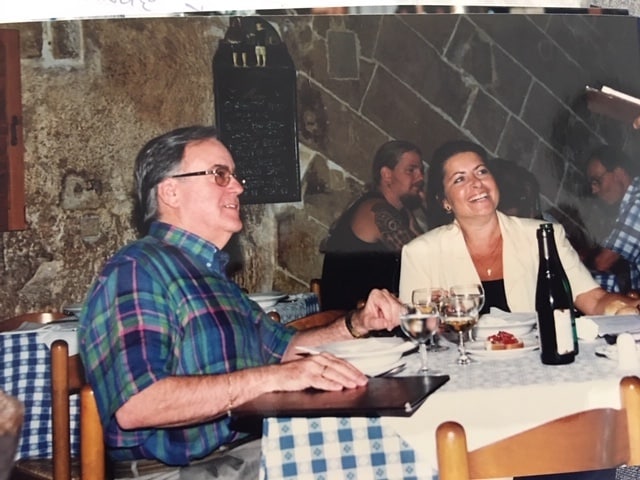

Norman’s wife Josette Grech is another well-known broadcaster. They had been colleagues since 1974, having what he terms a ‘love-hate’ relationship, particularly when he became her boss. “We used to fight like mad. We were also friends and would tell each other everything”. It was when they started working together on Sibtijiet Flimkien that the friendship turned into something more.

Is it difficult to work with your spouse?

“It’s difficult because you have to leave your problems at home. If you’ve just had a terrible argument you have to forget it for the sake of the viewers. You never allow them to see that you’re not the perfect couple. But we are like any other couple.”

While he would not say that either of them are prima donnas or suffer from an ego complex, he does admit that two presenters (whether or not they are married) have to be careful not to step on each other’s toes. In fact, in the last edition of Sibtjiet Flimkien they opted to do interviews individually. For next season he is going to go solo with something very different – a Saturday night musical show.

After all these years in broadcasting I wondered whether there ever came a time when he felt like chucking it all in? He sighs tiredly, yes. “Especially towards the end of a series, you say ‘I think I’ll stop.’ Then when the lean period comes, like now, you say I wouldn’t mind doing something.”

Are you easy to get along with or a pain? Better ask the others, he replies laughingly. Norman is frank: yes there were times when he believed that since it was his programme, he should have the last word. He has now come to realise that the producer should decide.

Norman does not fly into a rage easily. “I can take a lot. It takes a lot to irritate me. When I get very angry I shout, I flare up, maybe the occasional plate gets broken,” he adds dryly.

OK, so … what really gets your goat? “I get peeved when people come up to you, in a phoney way, slap you on the back and say ‘hey, all right? You had a good programme’ and then you hear that same person has been talking behind your back. You come to expect it, from colleagues especially, no matter which station you are with. Maybe it’s because I’m not at the beginning of my career, but I believe there is space for everybody in broadcasting. That people should be bitchy and want to grab everything for themselves is, to me, difficult to comprehend.”

Perhaps Norman is rather nonchalant about the business because there was a time when he was forcibly ousted from the work he loved. Then, he missed it, and missed it terribly.

Let’s talk a bit about the Xandir Malta episode, I suggest. Norman gives a short laugh. He gives me a chronology of the events:

It’s the day after the elections, 1987 – Norman, then Head of Programmes, is told to go home and not come in the next day which he didn’t do because he was suspicious that something was up.

Day Two – his office had been moved to another room facing the stairs. The running joke among the staff was that the next step would be that they would throw him down the stairs.

Six months later – Two charges were issued against him leading to dismissal, one of which was that he was infringing his position and giving programme material to Antenna magazine, Gwida magazine’s rival. “What happened was that I directed Antenna to write to the programme distributors abroad who would then give them the information. That’s all. But they found me guilty of that and threatened a transfer. However, Anglu Fenech and Lino Debono asked for an appeal – meanwhile, pending the appeal, I was to stay at home with full pay. It was very humiliating. I had to do something otherwise I would have gone mad.”

“I sought advice and found I could be a tour leader. Sure enough, another charge came out saying that I was doing part-time work without permission. Then another charge came out because they saw me at the television festival in Cannes where I was helping out. They said I was duplicating my work, which didn’t make sense because I was not Head of Programmes anymore. Then they invented a post that didn’t exist – Head of TV Licenses – with 8 cashiers, in one room at City Gate, next to a public toilet. I took it for about a year – that was the most humiliating, I think.”

But like all bad episodes, a change of luck was just around the corner. Although he had consolidated his tours, he was not yet ready to go full-time. Super 1 was starting up and wanted a Marketing Manager who would also be a presenter. “I said OK, I’ll resign. Everyone said, ‘don’t give them the satisfaction’ (Tpaxxijhomx) but I did it for myself. I took the Super 1 job for just over a year until I opened the travel agency.”

It was some story, and one which has been repeated countless times by both Nationalist and Labour administrations: competent people being victimised for their political beliefs. A sad indictment of the pettiness of our politics. Norman, however, has this to say (please print this, he tells me): “To whoever tried to humiliate me so much, and harm me and my family so much, thank you. Because if not, I would probably still be Head of Programmes at Xandir taking orders from whoever is in government, always being clouted about the head.”

The main course arrived just in time to alleviate the bad taste left behind by this story. We had ordered fresh sea bream. A platter of spring onions, marrows and green peppers and roast potatoes in olive oil were the side dishes and everything was delectable. Norman is a very slow eater, and to my shame, I am not. He enjoys and savours his food (as you are meant to) and I tried to follow his example.

Norman takes up the last thread of the conversation: “For a while I kept saying, but why, but why – was I so politically involved? As far as I know I wasn’t heavily into politics in those days. But the fact was that Sibtjiet Flimkien came into being to break the infamous boycott of the ’80s. I was asked to create a programme which would get the small businesses to come in as against the big boys who were boycotting us. So I took my four hour radio programme Sibtjiet Sajfin and suggested we translate it into television. We could sell each short segment to advertisers.” (Aha! So Norman Hamilton is the reason we have a messagg promozzjonali every time we blink!).

While it immediately proved popular with the viewers, Sibtjiet broke the boycott completely when it introduced football matches, such as the FA Cup final, via satellite. “Everyone wanted to advertise because they knew people would be watching football.” While the programme represented a personal success, the irony was that the breaking of the boycott was what ‘broke’ Norman: “someone wanted to pay me back” he believes.

When I ask him whether, after all that has happened, he would ever go back to what is now PBS, Norman does not answer right away. “I tell you why I hesitated” he says finally. “I always thought I would want to go back for three months, get what was due to me – and then leave it. But now – no.”

I suppose it is in human nature to want to repay ‘in kind’ those who have done us wrong (I can think of a couple of people myself right now), but revenge, Norman says, is not his style. And he is right – perhaps the best ‘revenge’ is to succeed in spite of the obstacles put in your way by those who have tried to crush you. If nothing else, Norman Hamilton is a survivor.

The irony of it all is that he is not even politically active. Once upon a time, he tells me, he was approached “a bit like Bundy”, to contest the elections. Reluctantly, he started door-to-door canvassing, but soon realised he was making a lot of enemies with established candidates in that district, which dismayed him. “People who used to talk to you become your enemies – if that’s what politics means, then I’m well out of it. Everyone knows my political leanings, but I’m not active in politics.”

In Maltese we have a saying kemm jien bezzul (which incidentally, was also turned into a song). A very loose translation would be “Things always seem to go wrong for me.” And it is probably safe to say that Norman has uttered this phrase more than once in his lifetime. After such a long career in the music business, he seemed a natural choice to be appointed Chairman of the Song for Europe Festival Committee. His term was very short-lived however, 1997-1998 to be precise.

“I was appointed just after the ’96 elections (which were won by Labour) . I loved it, it was a challenge to me; I love Maltese song and anything to do with music. When the government changed again in ’98, I followed normal procedure and resigned. But nothing happened, I asked to speak to the (now PN) Minister because in October we had the International Song Festival in Gozo. I kept sending messages to the Minister to see whether I’m going to be there, if I should cancel everything, but he told me “Le, just keep going, business as usual”.

So he did. Soon it was time to prepare for the Song for Europe. But in the meantime, he went to Los Angeles to judge a FIDOF contest. He got a call from John Agius from L’Orizzont: “We would like your comment about the fact that you have been removed from the Chairmanship.”

While he had been expecting it, he had not been expecting it to happen while he was abroad, and without being formally informed. The press conference was held announcing the appointment of the new Chairman and when Norman returned he found a letter with the news. He sighs again; “these things shouldn’t happen. For someone not to have the guts to send for you, tell you thank you, and say ‘listen you can understand our position’…”

Frankly, I find the whole issue of politics entering such innocuous committees as that for the Song for Europe, highly ridiculous. I even find it absurd that each year, festival presenters are carefully chosen to ‘represent’ both parties. While Norman agrees on this point, he also admits it was one of the things he didn’t change. As I shook my head at the banality of this, Norman comes out with a phrase I have often heard before “This is Malta…you cannot change the mentality.” (Well, someone should at least try…)

Although I consider him as one of the few who have made the successful transition from radio to television, Norman does not totally agree: “Wait a minute. At the beginning I was given programmes which I didn’t used to feel and I always used to flop. I felt that I flopped completely, always. I couldn’t do it. Sibtijiet Flimkien was something I felt because I had originated it on radio and knew exactly what I wanted. After five years of that, you get the confidence you need.”

Just as his single-mindedness had brought him a successful career in broadcasting, it stood him in good stead again when he opened Hamilton Travel. He loves a challenge, “typical of my sign, Taurus – the bull goes in where angels fear to tread. I take a gamble, yes.”

In a career which has spanned over 30 years, he has seen a lot of changes in Maltese broadcasting. We talk about pluralism: “I believe that whoever applied for a radio licence should have been given an identity. If you tune in to any radio station now it’s like a jukebox – they’re all trying to get the same listeners. My idea of pluralism would be to have an easy listening station, a rock station, classic station, talk station, country and western, jazz to attract various pockets of listeners. Instead, it’s a hodgepodge, ejja ha mmorru, everyone gets a licence! Calpyso is the only one which tried it with middle-of-the road music.”

At 50-something, Norman is the proud father of Davinia, 13 and Yasmin, 8. ” Every man, I think, has a dream of becoming a father. I would have liked to become a father at an earlier age, maybe I would have had more patience with the children. But I’m happy to say that I’ve seem them growing up, as against a lot fathers to whom work comes first.. They both do well at school; Davinia is always first in English” he adds, with open pride.

Despite his media success, deep down Norman claims he is still an introvert; it was broadcasting which helped him to come out of his shell. “I’m not easy facing people I don’t know so well; people expect me to know them. I am not really a good socialiser. I get tongue-tied – people don’t expect me to be shy, but I am”. And that well-known voice, so immediately familiar to viewers and listeners, stops for a moment and we (slowly) resume our meal.

- August 9, 2023 No comments Posted in: Let's do Lunch Tags: Norman Hamilton