Children invisible in Family Court decisions

Adults perceive children as naïve or incapable of understanding

The family court justice system is failing to listen to children’s voices and to act in ways that reflect the reality of their lives and their best interests, a new study released today finds.

Interviews with youngsters, who have gone through the system, bring to light a troubling situation where children are being left out of decisions that shape their lives, even when they understand, feel, and suffer the consequences very deeply.

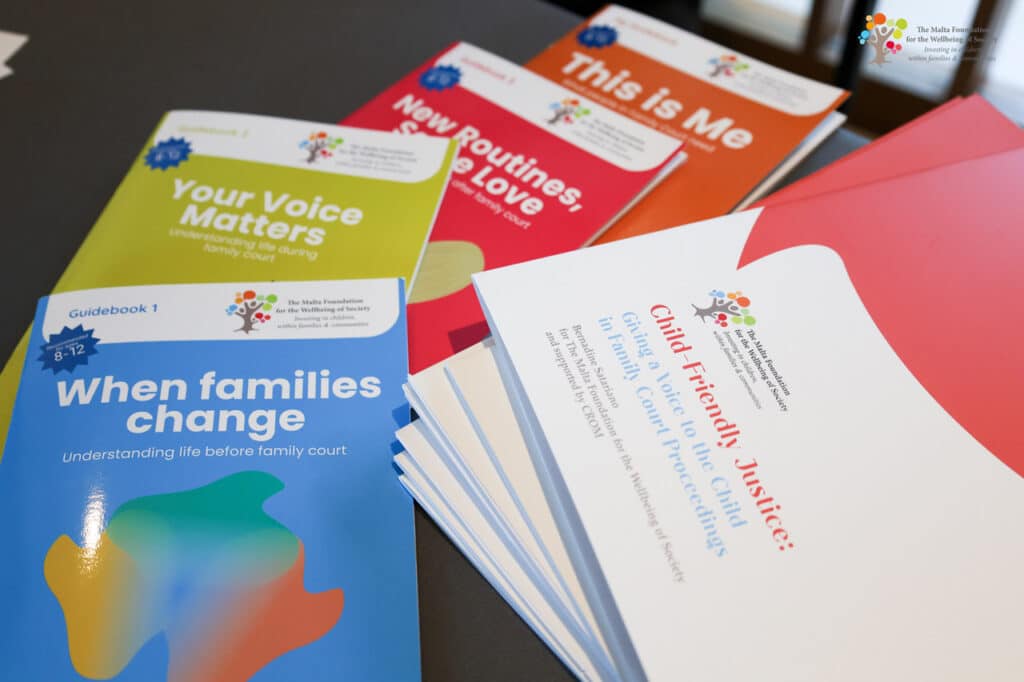

The qualitative study, titled Child-Friendly Justice: Giving a Voice to the Child in Family Court Proceedings, was carried out by lecturer and researcher Bernadine Satariano for The Malta Foundation for the Wellbeing of Society and supported by the Children’s Rights Observatory Malta (CROM).

Dr Satariano said: “Across the interviews, children’s constant narrative was, ‘They left us out’, repeatedly saying the most painful thing for them was that ‘no one explains anything to the child’.”

This study, presented during a half-day seminar addressed by Justice Minister Jonathan Attard and MFWS chair Marie-Louise Coleiro Preca, explored how children’s experiences within the Maltese Family Court system were shaped by the opportunities and barriers to their participation.

Apart from the research, guidebooks to support children and parents during the separation process were also presented.

Ms Coleiro Preca urged the courts, policymakers and authorities to be bold to push forward the necessary changes because the present family court justice system was clearly failing youngsters.

“Changing routines and existing standard solutions, such as alternating weekends for custody that may disrupt a child’s life, is difficult, even when everyone agrees in principle. But with leadership, time and political will I’m optimistic we can make a difference,” Ms Coleiro Preca said.

“Society still underestimates children’s competence. As long as the adults and professionals keep saying ‘they’re too young to understand’ or ‘we’re protecting them by not telling them’, the system will continue to be designed to talk about children, around children, but not with the child,” she added.

Set up in 2003, the Family Court has evolved, but despite the progress, the system’s improvement has been inconsistent. Children feel invisible and their participation remains vulnerable to the goodwill of individuals rather than protected by an established policy system.

Through interviews with social workers, psychologists, mediators, lawyers, child advocates and the youngsters themselves, the research aimed to understand how, and by whom, children were heard during their parents’ court cases, and how institutional, professional, and familial factors enabled or hindered their voices.

Dr Satariano said many children described meetings that would determine their whole lives barely lasting 10 minutes; while professionals spoke of the absence of accessible channels where children could independently seek help.

During the interviews a constant narrative emerged where all ex-child participants said adults perceived them as naïve or incapable of understanding what is happening within their families.

The absence of clear, child-friendly explanations was also leaving children between conflicting parental narratives, unsure of what the court had actually decided about their future.

One child’s statement debunks the court’s presumption that children should be silenced, as they do not know what is best for them or what is safe for them. “I was aware of what was happening at home… the fighting, the arguments, the domestic violence. There was no one who supported me or heard me… my mother used to burn me with her cigarettes when I was very young. But no one believed me that my mother did not love me.”

The court’s failure to engage directly with children also allows abuse to remain hidden behind the rhetoric of protection. This dynamic was echoed by a young man, who narrated the impossibility of self-advocacy within the court’s assumptions.

He said: “Most of the time, the voice of the child in court can only be heard through the parents and the lawyers… but if you are abused by a parent, how on earth does the court assume that as a child you will report it. Do you think a child has the courage to go beyond and report their parents? I did not have that courage.”

Was Dr Satariano surprised by the outcome of this study? Or did it confirm what she already knew?

“Both. On one level, the results confirmed that children understand far more than adults assume, and that our system is built around adults, not children. But, what did surprise me was the depth and consistency of harm.

“This was not just an isolated negative experience, but children feel they are ‘born unlucky’; they are forced to move ‘like a ping-pong ball’ between homes; they are terrified of abusive parent/s; they are threatened with having their police conduct tarnished if they speak. These constant feelings of injustice, harm and pain are prevalent across all participant young adults who went through family separation,” she explained.

Dr Satariano urged policymakers and the court to listen to the children and to stop underestimating their competence.

“Children see everything. They see the abuse, the manipulation, the financial battles, the depression, the alcohol, the gatekeeping. Age does not determine if they can understand their family situation, age only limits their varied vocabulary and the possibility to narrate details.”

- December 10, 2025 No comments Posted in: Education Tags: children, family court