The man who would be king

After watching a press screening of Dear Dom, the documentary produced by Pierre Ellul, my one recurring thought was, how did a man who was so well-spoken and so well-dressed at the beginnning of his political career, turn into the shouting, gesticulating dictator-like figure wearing a huge buckle and flannel shirts towards the end of the film?

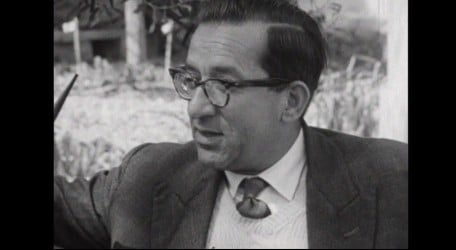

In the footage taken from the 1950s, Mintoff, with his sharp suits, his pipe and his mischievous smile, almost had a certain charm, and his political arguments were persuasive. You could see the charisma everyone always speaks about, and you could comprehend how he managed to lead his supporters in the fight against the mighty Catholic Church in the 60s. It was an unthinkable task, given the stranglehold which the Church had over Malta in those days, not only culturally but politically as well. Yet his avant garde ideas of the need for more civil liberties and social justice for all, which were so far ahead of his time, struck a chord with those who were left-wing in their ideology. For many people, the need to bring about a separation of church and state simply made sense. The fact that we are still not there yet today only underlines just how revolutionary he was.

What went wrong, of course, was that Mintoff was simply there too long. He overstayed his welcome, and the longer he was in power the more infallible he thought himself to be and the cruder his methods became. As someone pointed out in the documentary, every issue had to turn into a fight and it was either his way or nothing. The thought occurred to me during the film that as the years rolled by he started behaving more like a king than a Prime Minister, and maybe that is how he ended up thinking of himself – lording it over Malta as if it were his, smiling benevolently at his subjects but only if they swore their undying allegiance and loyalty.

I have often thought that Malta should adopt the US model, where the same politician can only serve as the leader of the country for two terms. In the US this means a total of eight years, whereas here it would mean two five year terms. I’m no expert, but I do not think this would require much effort. The political parties merely need to agree that after a Prime Minister has served two terms, he must step down as party leader, and if the same party is voted into office again, then it would be with a new face.

Surely ten years in power is more than enough for anyone? It is surely enough for any country, because it avoids the inevitable cult status which surrounds a leader who is in our face for decades. Mintoff gradually become and more of an untouchable icon; a situation which reached its peak in 1976. After that, his cult figure status became so entrenched in the public psyche that it lasted for the next ten years with devastating results. Watching the adulation of his supporters made me squirm with unease; seeing the other Labour politicians and dubious-looking canvassers jostling for a prominent position whenever he spoke to the masses was even worse.

For, as we have seen time and again, not only is it dangerous to have the same politician at the helm of a country for too long, but it is not in the country’s interests to have the same hangers-on clinging to his shirttails either. The power which was wielded by Mintoff was considerable – and by association, anyone who was on his side (and in his favour) likewise wielded power. I do not need to go into the details of how it all spiraled out of control – this very well-produced documentary manages to convey the ensuing political violence in brief flashes of graphic imagery. They are all the more powerful for what they do not show.

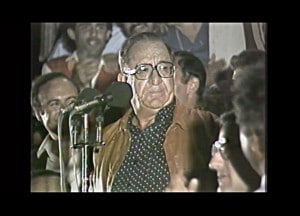

With each election, the underlying tone of Mintoff’s speeches became less about the issues and what was good for the nation and more about him being right and everyone else being wrong. His use of inflammatory language and wild arm gestures signaled that he was losing his grip on the island. In the end, it was clear that he was simply desperate to hang on to his throne.

On the whole, I think Pierre Ellul and the team behind him, did a fair job of portraying Mintoff in his glory days as well as depicting the series of unforgettable events which led to his downfall. Perhaps the most striking moment in the film was when it segued from the crowds of supporters chanting ‘ma taghmlu xejn mal-perit Mintoff‘ during his heyday, to the cries of ‘Guda, traditur‘ by some of these same supporters when Mintoff brought down Alfred Sant and his own beloved party in 1998. It is one of life’s truisms that the same people who put you up high on that pedestal are usually the same ones who rush to knock you down when they feel you have betrayed them.

Prior to watching the film, I had heard skeptics say that this documentary is simply a well-timed propaganda exercise to remind people once again of the more unsavoury aspects of the old Labour party. Having watched it for myself, I cannot agree. I feel it was probably the first really objective account of those turbulent years in our political history, and I believe it did manage to scratch under the surface of Mintoff and portray him accurately, warts and all. According to the producers, there were people who were approached to speak about their disagreements with Mintoff but who did not wish to do so on camera because they were afraid of retribution. This I cannot understand – afraid of whom? Lorry Sant’s ghost? The phantom of Il-Fusellu? Surely that type of political thuggery is no more.

My own theory is that they were reluctant to go on record for another reason: the fear of their interview being used as a political manoeuvre. Will carefully edited excerpts from the documentary end up being used and possibly manipulated in an election campaign, for example?

For the producers’ sake, I hope not.

The greatest pity about this documentary is that Pierre Ellul never managed to interview Mintoff himself, which according to his production notes, he attempted to do several times. Dom Mintoff is notoriously difficult about granting interviews – I had tried several times and he just shouted at me gruffly over the phone, demanding to know who the heck I was.

Now that he is no longer able to give interviews, the countless questions we all have will probably never be answered.

Whether you hate Mintoff or love him, I recommend you go watch this film with an open mind. It provides much food for thought not only about our political past but, just as significantly, about our political present.

Dear Dom opens at Eden cinemas on 23 March.

- March 10, 2012 18 Comments Posted in: Opinion column