Capturing the 80s

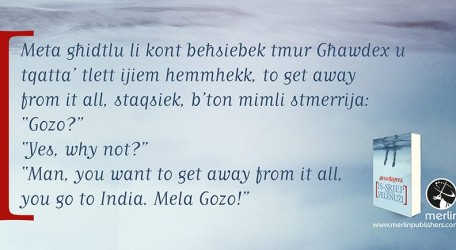

This morning I started reading Is-Sriep regghu saru Velenuzi, by Alex Vella Gera, which will be officially launched this weekend by Merlin Publishers.

Last night I also watched the interview with the author himself on Bondiplus, which gave a whole new twist to the book itself. It is not often that one is given an insight into the author’s mindset before a book actually hits the shelves, so kudos to the publishers on landing this interview on prime time. That’s great marketing.

I’m enjoying the book immensely, because Vella Gera has the knack of painting the socio-political turmoil of the 1980s, and all that it meant for us in Malta, with a few swift but precise brushstrokes. His skill in effortlessly switching back and forth between Maltese and the patois English so often used by English speakers, not only in the characters’ dialogue but also in what they are thinking, is exact. He brilliantly captures the Malta of 1986 and, of course, today’s Malta as well (here I cannot agree with Lou Bondi who said that the language issue is no longer relevant today; oh yes it is Lou, our choice of language, and the pronunciation of it, as well as our syntax, will always continue to define who we are and where we come from).

Phrases in the book leap out at you and take you back to those times: “They’re with Mintoff those! Mama told us not to speak to them,” says a six-year-old boy, who despite his age is already keenly aware that Malta is divided into “us” and “them”.

I will not give away too much about the book so as not to spoil it for those who wish to read it for themselves. I do wish, however, to go back to Vella Gera himself and what he said last night. He freely admitted that he left Malta because he wanted to escape it, and yet his work as a translator in Brussels, his Maltese colleagues and his use of Maltese as a literary tool add up to a glaring paradox. Shaking his head in self-bafflement, he agreed that it does not make sense to him either, how his roots and identity keep him so firmly tied to the land he wanted so desperately to turn his back on, but which draws him back time and again. Having said that he also acknowledges that he feels strangely detached from today’s Malta; he does not really know it at all, except from what he reads online, which can only give him a warped reflection of reality.

I find this internal tug-of-war quite common among the new generation of emigrants who work within the framework of the European parliament and other related institutions. Unlike those who emigrated in the 50s, this crop has not made a clean break from the island. I have concluded that it has something to do with their very profession, and their daily use of Maltese as a tool of expression which has led several of them to write books in Maltese, using their 1980s childhood as inspiration.

What I also found interesting about Alex Vella Gera’s interview is his often curious expression when Lou Bondi kept harping back to the sexual scenes in the book. “This is no 50 shades of Gera”, the author quipped with a slight smile.

Apparently there are some quite graphic sex scenes which I haven’t come to yet, but as the author pointed out these have not been included gratuitously, but are there simply because sex is part of human nature. “If people are going to just look for the sex scenes, they will be disappointed,” he added wryly.

Another thing which struck me was Vella Gera’s honesty when it came to describing how he evolved in the way he looked at people who come from different backgrounds to him. As he pointed out, once you start actually speaking and interacting with those of a different political persuasion to yourself, instead of stereotyping them and dismissing them, it is easier to understand where they’re coming from. I felt like applauding him on this. Boxing people into “types” is one of the biggest problems this country continues to face and it often colours our prejudices unnecessarily, making us even more insular than this bubble of an island already is.

I plan to write more in detail about the book when I finish it, but from what I have read so far, this promises to be one of the best and most truthful Maltese novels about the 1980s ever written. And if we are ever to get over ourselves enough to look at that era with dispassion, we need more insightful authors like Alex Vella Gera.

- October 17, 2012 No comments Posted in: Hot Topics