Simone Spiteri at Cafe Jubilee, Gzira

She’s a talented actress, a gifted playwright, runs her own theatre company and is the recently appointed consultant/drama director at the Manoel Theatre. At the moment she is busy with rehearsals for the upcoming production Kjaroskur, which she not only wrote, but in which she has a leading role.

And those are just some of the things she does in her spare time, because her ‘day job’ is that of an English teacher.

And yet to look at her, Simone Spiteri with her slight build and a pouch slung over one shoulder, looks too young to be handling all this. She seems as calm and unruffled as someone who only has one thing on her plate instead of ten. By her own admission she is “almost too organized” and this is perhaps what gives her the poise of someone who is in complete control.

We have met for lunch at Café Jubilee, the Gzira outlet, the perfect place for a casual lunch for people with a busy schedule. Laidback and unpretentious, the retro décor is reminiscent of a pub with chalkboards announcing the day’s specials and booth seating which give you a chance to talk privately.

Simone’s new role at the Manoel has given her the opportunity to push forward new initiatives such as writing and directing as well as to act as a go-between with those companies producing plays at the national theatre. While she is there, to avoid any conflict of interest, her own company Du Theatre, will not be involved in any way with the Manoel.

As the eldest of three children, it was ingrained in Simone to be the responsible one. She was always creative and summers were spent outside running around with the other children. “From the time I was 10, I used to write plays for my friends and we used to put them up. I was a happy child and had a great childhood.”

Like most writers she is a voracious reader; she says that the promise of a new book was the only reason she used to agree to go toVallettawith her aunt every Saturday morning. She doesn’t know where her theatrical streak came from but counts herself lucky that she attended the school in Zejtun where Trevor Zahra was a teacher and where they had a strong drama department. “I was swept away by the whole theatre thing.” Ironically enough it was the reaction of a school guidance counselor which spurred her on to pursue her dream. “I asked her what subjects one had to choose to become an actress and she just sniggered. I was so angry! Now, I’m a quiet rebel, not the type to shout, but inwardly I thought, ‘I’ll show you.’”

Her parents were supportive although there was a tiff with her father when she chose theatre studies at University rather than something more practical like law or medicine. But Simone knew what she wanted and stuck to her decision. “Now that I’m older I understand them – it’s not their world. But today they come to all the plays and are very proud.”

She started attending the Drama Unit at the age of 13 and spent eight years there, meeting a lot of the people with whom she eventually set up her company. At the age of 20, fresh out of University, she set up Du, mostly because of a dearth of good scripts and roles for women. The name is a phonetic version of the word ‘do’ – “which is what I’m all about”.

The company produces a lot of plays which are female-centred for the simple reason that it is very hard to find male actors. “At drama school we were about 15 girls and two boys, it’s always been like that!”

The first play she ever wrote was for the Dramafest at the school, an initiative by Josette Ciappara, which encouraged the budding thespians to submit original 30 minute plays. When hers was chosen, she had two months to produce it – when she couldn’t find a male actor, she recast the role for a female, more actresses joined the company and Du was born.

“It ended up becoming a sort of a winning card because it was different. And when it came to the work it gave a completely different twist to what we were doing. The dynamics are not the same when you are writing for just females, or when you are rehearsing with just women. You tip the balance – as soon as you have a male on stage you tend to want to address the male/female relationship, but when it’s only females it becomes very interesting.”

Simone was never formally trained as a writer, but the many hours she spent backstage gave her a holistic view and a very good grasp of what goes on during a production.

“I was always hesitant about calling myself a writer because I was not doing anything official or formal about it. It took me a long time to say on a Du poster that I actually wrote the play because I felt I had to earn the audience’s respect first. After all those years at drama school we were all quite intense about just going for it and producing good theatre. For me, at first, it was more about being in a play that I chose and wanted to be in, and not staying at home waiting for a call to be in a play that I didn’t necessarily like. When we settled a bit, I realized that I could explore more with my writing. However, even now, almost ten years later, there is always that amazing feeling when I look around and realize that there are 15 people who are involved in this because of something which I put on paper. The level of trust is incredible.”

Does it scare you?

“Yes, because it puts pressure on me,” she admits candidly. “I’m 28 now, but to think how young we were when we started, it hits me that we must have wanted to do it so much that we did not stop and think about the pressures at the time.”

Anyone in theatre knows that finding financial backing is the biggest obstacle, but Simone tells me that starting off without a cent meant they had to be creative when it came to production costs. “Our costumes came out of our own wardrobes, and our props were what my Dad put together from scraps of wood. That really helped us because it didn’t give us anything to hide behind – it was just us; it was either good or bad.”

Since her award-winning and highly acclaimed play Appuntamenti last year, Du theatre has taken a bit of a break. Most of the group have got married and had children. Now that they have regrouped, older and wiser, they ask themselves how on earth they used to do three plays a year. “We were crazy,” she says simply.

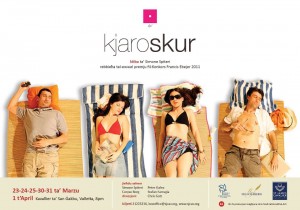

The fearlessness of youth, of course, makes one just plough forward and do things – now with maturity comes the knowledge that they have to live up to people’s expectations. Kjaroskur (which won Simone the Francis Ebejer prize for the second time), took her almost a year to write.

“After Appuntamenti, people kept asking me ‘so, what are you going to write? Now keep writing!’ so it was a lot of pressure and it took a bit of time for me to sit down and do it. The break was good however because I traveled and did other things.”

Two years ago she won a scholarship to Stratford-upon-Avon which immersed her into the heady, intellectual world of Shakespeare with workshops and going to performances and analyzing them afterwards with professors.

“I was watching A Winter’s Tale which is about how a man misinterprets his wife’s actions and how it creates a domino affect. It struck me that it happens a lot in Shakespeare that you have this main actor who takes everyone along with him because of one event. So I wondered, what would happen if we had to take Hermoine’s point of view for example? If she had been given the chance to explain her side of things earlier in the play, it would have changed everything. And it’s like that in life as well. Something could happen right now in front of us but we would both give it a different interpretation according to our own baggage. That was what led me to write Kjaroskur. I wanted to explore the repercussions of when something trivial happens and everyone sees it differently. It’s set in a farmhouse in Gozo, very contemporary, with four normal people and the theme is universal. However, it is very technical because you are hearing the story from four different points of view and the audience has to piece it together. I hope it works,” she adds, taking a deep breath and revealing a hint of nerves. “From page to stage is a big step.”

I ask whether people her age are into theatre. “I don’t think it’s a social habit yet; it’s not their usual night out. But then again, with Appuntamenti we had a lot of people who had never been to the theatre before. I really appreciated the word of mouth advertising, because to have someone attend who has never stepped into the theatre is amazing. There was this group of 20-year-olds for example, who told me ‘thank you, because we thought that theatre in Maltese is boring, traditional and archaic’, and that was a real compliment.”

Simone is a fluent and very articulate English speaker but she makes a conscious effort to write in Maltese, “I think I express myself better in my mother tongue and I feel a certain duty somehow.”

While there has been a surge of young novelists in Maltese who are reflecting today’s Malta, what really baffles Simone is that no one seems to be writing plays about all that is happening on the political, social and anthropological level in Malta.

“There is so much to write about; the experience of being Maltese and living in Malta. Unfortunately in the last 20, 30 years we have only been importing foreign plays and writers took a back seat and are not writing. We cannot go back and say let’s see what was written in the 90s or in the last ten years.”

Have you ever thought of leaving Malta?

“Ah, the million dollar question! Yes, many times. I travel a lot and it’s not something I rule out. If I ever had the opportunity I would take it, but only for a few years; I don’t want to spend ten years in another country, for example. Although I need to get away because I feel claustrophobic, I admit I do love coming back. Malta is a good place to have as a base for theatre, actually.”

Because she spends a lot of time thinking about what she is going to write, Simone is a fast writer, very sure of what she wants to say and impatient to get to the rehearsal process and see her work on stage.

“I’m not one of those people who enjoy the act of writing and have ten drafts of the same thing. I try to let the script breathe – I try to understand what I want to do and who the characters are. I don’t give them a voice; I listen to what they want to say. By the end of the play they end up being completely different to what I had planned. I know where I’m going to start from and where I want to get, but in between I let them speak for themselves.”

Like most introspective writers Simone loves to watch people quietly and observe their behaviour, taking in her surroundings. “I’m hardly the life and soul of any party. But you have to be observant if you want to write about things you haven’t experienced yourself. I don’t know what being in a marriage is like, but I write about it, and the actors in the play who are married tell me, ‘I’ve had this fight many times, how can you know about it?’”

Understandably, as an actress, it would be “torture” for her to sit and watch the play and not be in it. She is not possessive about her work, but is quite willing to have the other actors change and alter dialogue which does not sit right. “You cannot be too precious about your script. After all, if an actor is not convinced of what he’s saying it’s going to backfire – I like to listen to what they have to say. We have cut, edited and changed as we went along. Before going into production I always send my script to people whose opinion I value because feedback is so important. You get so immersed in your own work and I have completely lost my objectivity now; I have no idea how this looks to a pair of fresh eyes. Now that the crew has joined us I pounce on them, ‘what do you think?’ I believe in engaging people – the only thing that classifies good theatre and art is if you establish a connection.”

She is very pleased to have Chris Gatt on board as a director as he comes up with things she never even thought of, giving it a new perspective.

“At some point from now until we have our first performance I’ll have about ten moments of panic, ‘what the hell was I thinking?’ Because when you think about it, you would be hassling and stressing over an hour’s worth of work, which goes by very quickly. All those months and hours which you’ve put in – it’s quite a cruel art form, not like a painting which is going to stay there. Theatre is something you can never recreate.”

Simone Spiteri, Coryse Borg, Peter Galea and Stefan Farrugia play the lead roles in Kjaroskur which will be on at St James Cavalier 23,24,25,30,31 March and 1 April at 8pm. Directed by Chris Gatt

WHAT WE HAD FOR LUNCH

Mediterranean Chicken with penne – grilled chunks of chicken breast, sundried tomatoes, pine nuts, rocket and cream

Chicken Rucola – grilled chunks of chicken breast, sundried tomato paste, pine nuts and mozzarella with a rocket leaf salad

- March 19, 2012 No comments Posted in: Let's do Lunch